Confidence and Coaching: The growth of my confidence as a coach and the neuroscience behind that. Part 1 by Andrew Parrock

My coaching journey

I remember when I first discovered that I had been accidentally coaching. I had been mentoring people, and often used a technique that I had used as a teacher; asking questions to get my student to think for themselves and reach their own conclusions. I knew this worked, from practical experience, but did not know that this technique was central to coaching. I was confident in my approach, knowing how and when to use it.

Later, when I was doing my formal coaching training, learning about GROW, about empathy, listening and being non-judgemental, my confidence dropped. I struggled to balance all the new ideas in my head, at the same time as applying them in practice. I found I was slower, more focussed on, for example, applying GROW. The whole experience felt less like a conversation than it had previously when I was unaware that I was coaching! I had come across the four-stage model of learning [ref 3], so perhaps I should not have been surprised. But what did surprise me was the effect the formal learning process had on my confidence. The nagging doubt surfaced in my mind, “can I really do this?”.

I persevered, read around the subject and, most of all, remembered and focussed on the vital point that I was there for my client. I gradually dropped the formal application of GROW and allowed myself just to be there with my client, listening, thinking about what I could say next to help them. It started to feel more like a conversation again. Following a discussion with my supervisor I started to ask for feedback from clients and discovered that my approach was working for them. My confidence began to rise.

I have seen new coaches in the internal programme I run start out in much the same way. They come to our regular Action Learning Sets and ask the group how they can possibly balance all the things they need to do in our heads and still relate to their client. The question always sparks a lively discussion about the practical details of what happens during a coaching session, for both coach and client. What lies behind those questions is always their confidence in their ability to coach.

Through my coaching practice of experience, reflection, and keeping up with developments in scientific knowledge about how the human brain works, I have realised that confidence is something I have that can change over time, and fluctuate both up and down.

But what is confidence?

Would knowing what it is help to make us better coaches?

This is what I want to address in this article.

What the current scientific understanding tells us about where confidence comes from.

How confident am I in my coaching?

This was a question I had never asked myself. I was aware that my confidence was increasing, but my reflective practice looked at what I was doing; my approach to coaching and the tools I was using during my coaching sessions, not my confidence, which I regarded as something that ‘just was’.

Then I read ‘Know Thyself: the new science of self-awareness’ by Stephen M Fleming [ref 1]. His book has inspired my two earlier blogs about the application of metacognition (this science) to coaching Part 1 and Part 2 [ref 2]. It has now inspired this one, which is about self-awareness and confidence, how someone’s confidence in themself can be wrong, and can change. Also, how we, as coaches, might apply that knowledge to improving our coaching practice.

This is a huge topic and so I’ve broken this down into the following parts for my series on confidence and coaching:

The first looks at the current science (more correctly, my understanding and, no doubt, misunderstanding, of the science) that describes the first of two underlying mechanisms – self-awareness and metacognition that produce a feeling of confidence in a person.

In the second, I look at the second mechanism – emotions that influence and affect someone’s confidence.

In the third, I look at how we might use this new knowledge to improve our coaching

The science

Our feeling of confidence emerges from our self-awareness in ways that we are not conscious of. By understanding something of where confidence comes from, I am hoping that we can become more consciously aware of the influences that affect confidence, and as coaches, work with those influences when we are working with our clients. For me, all this works with my coaching style, but it has made me more consciously aware of the influences, and so be able to describe them to my client. Where does self-awareness come from?

First, Fleming uses the terms ‘self-awareness’ and ‘metacognition’. They are closely related but subtly different things.

Metacognition is “any process that monitors another cognitive process…[it] may sometimes occur unconsciously.” He uses ‘Self-awareness’ to mean “…the ability to consciously reflect on ourselves, our behaviour, and our mental lives.” [ref 4]

A fuller description of where self-awareness comes from can be found in my earlier blog, ‘Metacognition; thinking about thinking in the context of my coaching practice (Part 1)’ [ref 5]. But to summarise drastically, human metacognition is believed to emerge from the two building blocks of ‘sensitivity to error’ and ‘self-monitoring’, which are systems that take information in from the world and process it, and to allow us to perceive the world in which we live and act in that world. A vast array of neural autopilots continually adjusts our actions to keep them on track. Most of this is unconscious, in that we are not aware that it is happening. In fact, we don’t even know that it exists for us to be aware of what is happening. It is likely to develop from a genetic ‘starter kit’, and on the culture in which someone grows up.

Mutually reinforcing interaction between relationships, language and an expansion of the capacity for understanding what other people are thinking led the human brain to acquire a unique capacity for conscious self-awareness; the ability to think about its own thinking. This develops slowly, during childhood and adolescence, and it continues to develop during adulthood. It is sensitive to changes in mental health, stress levels, and the social and cultural environment in which an individual finds themself.

Self-awareness varies from person to person

The late Donald Rumsfeld is famous for having said;

“Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know….” [ref 6]

He was talking about the specialised field of military intelligence, but I think his words can be applied much more widely (and certainly more memorably), as a summary of our self-awareness. For example, when asked a question, usually about some fact, I sometimes cannot recall that fact immediately. This is an experience so common that it has its own phrase (at least in English it does); the answer is ‘on the tip of my tongue’. This is a name for that feeling that I do know the answer even if I cannot immediately recall it. When this happens to me, I often say “it will come to me soon”, and usually it does, especially if I’m not hunting for it in my memory.

Fleming says that “people have an accurate sense of knowing that they know, even if they cannot recall the answer” [ref 7]

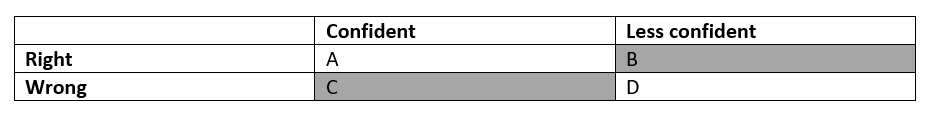

That sense of confidence is found everywhere our metacognition comes into play, whether it’s about learning something new, making a decision, or remembering a past event correctly. Experiments demonstrate that people with better metacognition have higher confidence when they are correct (Figure 1 Box A) [ref 8] and lower confidence when they make errors (box D). In contrast, people with poorer metacognition may sometimes feel confident when they are wrong (box C) or not know when they are likely to be right (box B).

Figure 1

Fleming does not make a specific reference to Daniel Kahneman when discussing this (he does later), but it did make me think of Kahneman’s ‘system 1 and system 2’. Kahneman specifically said that he was not saying that there were two dedicated neurological systems behind these modes of thought, he was using ‘system 1 and ‘2 as a convenient term [Ref 9]. But I am still left wondering whether having confidence leads more to system 1 type thinking in an area in which we have confidence, that is, fast and intuitive thinking rather than slow and deliberative thinking.

However, what these experiments have done, using this table over multiple occasions, to track the accuracy of a person’s self-awareness (i.e., their conscious reflection of an aspect of their mental life) about their own decisions, abilities, and memory. The more As and Ds, and fewer Bs and Cs, the better the person’s metacognition (that is, the, possibly unconscious, monitoring of those aspects of their mental lives). This is called their ‘metacognitive sensitivity’, which is subtly different from a person’s overall level of confidence, their ‘metacognitive bias’; someone may overall be overconfident, but if they are aware that they are wrong more often than not, then they will still have a high level of metacognitive sensitivity.

A person’s metacognitive sensitivity also does not appear to be related to their intelligence, as measured by IQ., as “the brain circuits that support flexible thinking (‘intelligence’) may be DIFFERENT from those that support thinking about thinking.” [ref 10]. So ‘confidence’ is another dimension to consider alongside IQ and ‘Emotional Intelligence’ when we are reflecting about ourselves.

Constructing confidence

When reading Fleming’s book, I was reminded of a documentary I watched recently on the BBC [ref 11], about the selection process for British Marine Commando Mountain Leaders, where the apparent confidence of the candidates was a key factor in their success or failure. This process is exceedingly arduous, both physically and mentally. At one point, the candidates have to jump over a huge drop with waves crashing on sharp rocks many metres below them. Any hesitation, even the slightest pause on the brink, led to the candidate being instantly failed by the instructors. Whatever the cause of that slight pause, the instructors take it to be hesitation, they conclude that the candidate lacks confidence. They want their leaders to feel confident and to project that confidence, to give confidence to the men under their command. Fleming later talks about how people follow those who APPEAR confident, whether they are or not. The army, I think, wants that appearance. (ref 15). The instructors took these outward signs of lack of confidence at that dangerous moment as an indicator of a future lack of confidence, which could well have fatal consequences for any future team looking to their commander for leadership.

That really got me thinking. Does a person’s current belief in themself breed future belief? Does success breed success? This idea has been around for a long time [ref 12]. It was first noted in Virgil’s ‘The Aenid’:

“Possunt quia posse videntur.” (They can because they think they can)

And, later, attributed to Henry Ford:

“Whether you think you can or think you can’t, you’re right”

This reminded me of Lynne Hindmarch’s good coach blog called ‘Self-Efficacy and Coaching’ [ref 13] which strongly supports that idea. Hindmarch and Fleming refer to the influential work of the psychologist Albert Bandura, who coined the term ‘self-efficacy’. Fleming refers to Bandura in Chapter 6 in a section called ‘Believing in Ourselves’ [ref 14]. A person’s belief in their ability to do a task (the ‘self-efficacy’ that Bandura described) is specific to that particular task. This self-efficacy has ramifications for our wider confidence. If, in early life, we stumble over a task, say, solving a maths problem, the belief created at that point affected their performance a few years later [ref 14]. This is ‘you can because you think you can', in action. (But part 2 will say a little more about this)

Conversely, in Ch 7, ‘Decisions about decisions’, Fleming explains how a dose of overconfidence can have a beneficial effect for its owner. Observing that

“...despite all the benefits of knowing our limitations and listening to feelings of low confidence, many of us still prefer to be fast, decisive, and confident in our daily lives- and to prefer our leaders and politicians to be the same.” [ref 15].

He describes studies by political scientists which show that, in simulated competitions for limited resources, overconfident agents tended to do a bit better than other agents, especially when the benefit of gaining the resource was high and when there was uncertainty about the relative strength of the different agents; “you have to be in it to win it”. The results became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Which, I think, is why the Marine instructors weed out those who hesitate, and selecting for those who believe, rightly or wrongly, in themselves.

Fleming further proposes that confidence emerges from the interplay between the two building blocks of self-awareness; our estimates of our uncertainty and our awareness about how successful our actions are. These blend to give us a measure of how confident we feel about successfully completing a task; our own actions are part of the input into our self-awareness of how confident we feel. Committing to a decision is sufficient to improve a person’s metacognitive sensitivity [ref 10]

Now that I understand something about the roots of confidence, I can recognise them in my own coaching. Having decided that I should ‘go with the flow’ of my client’s conversation and push formal models (GROW, for example) into the background, still there but not driving the conversation, I recognise that that decision, by itself, made me feel more confident about my coaching (at least, that’s how I remember it!).

Having an idea about where confidence comes from allows us to ask two questions, which I will address in my next blog in this series:

a) what can affect it?

b) what influences its development?

Andrew Parrock (MSc, CMgr, MCMI) has, since graduating in 1980, been a teacher, a tax specialist and a manager. He spent 10 years as a volunteer mentor with undergraduate students at UCL and, later, Brunel University as part of the National Mentoring Consortium. He discovered coaching late in his career and has now become an accredited coach at Practitioner Level with the European Mentoring and Coaching Council (EMCC).

References

“Know Thyself: the new science of self-awareness” by Stephen M. Fleming. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Know-Thyself-New-Science-Self-Awareness-ebook/dp/B08QRMXN2H/ref=sr_1_1?crid=1REO2TFDTNCFD&keywords=know+thyself+stephen+fleming&qid=1669826334&sprefix=stephen+fleming%2Caps%2C73&sr=8-1

https://the-goodcoach.com/tgcblog/2022/2/28/metacognition-thinking-about-thinking-in-the-context-of-my-coaching-practice-part-1-by-andrew-parrock and https://the-goodcoach.com/tgcblog/2022/2/28/metacognition-thinking-about-thinking-in-the-context-of-my-coaching-practice-part2-by-andrew-parrock

Know Thyself op cit p225 note14.

Andrew Parrock -op cit

Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/There_are_known_knowns#:~:text=Rumsfeld%20stated%3A,things%20we%20do%20not%20know.- accessed 11th August 2022

‘Know Thyself’ op cit page 78

Know Thyself’ op cit page 79

Daniel Kahneman; ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’ 2011

Know Thyself’ op cit p85-86

BBC 1, 21st June 2022

The Quote Investigator: https://quoteinvestigator.com/2015/02/03/you-can/ accessed 17th August 2022

Lynne Hindmarch ‘Self-Efficacy and coaching’: The Good Coach website, accessed 17th August 2022. https://the-goodcoach.com/tgcblog/2017/1/31/self-efficacy-and-coaching

Know Thyself’ op cit pp126-128

Know Thyself’ op cit pp 148-149